By Na Ma, Ohio University

Folk-inspired film usually underlines the significance of folklore for understanding African-American cultures and identities. For instance, Wend Kuuni (1983), emphasizes how film can adapt folk motifs in creating “a new order to replace the old and stagnating one” (Diawara 201). Another good example of using folklore in films is To Sleep with Anger (1990) by Charles Burnett[1]. As Burnett says, folklore has constituted “an important cultural necessity that not only provided humor but was a source of symbolic knowledge that allowed one to comprehend life” (225).

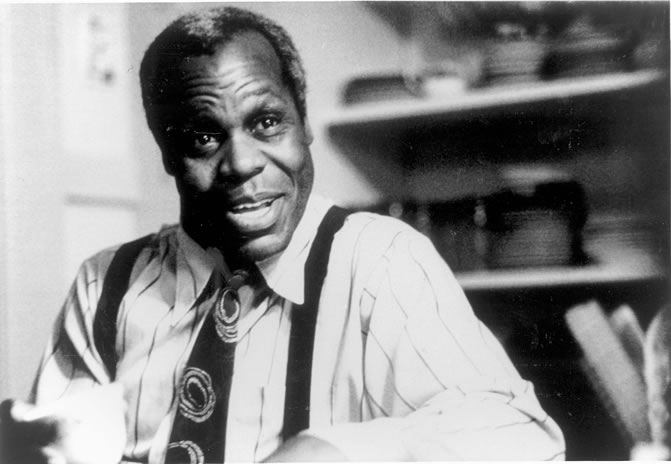

To Sleep with Anger (1990) tells the story about how a man named Harry (Danny Glover) disturbs his friend Gideon’s (Paul Butler) family’s (mis) functioning. It seems everything runs smoothly with the family until Harry’s arrival. When Harry comes to visit them, Gideon insists that Harry stay with them for as long as he would like. His disruptive presence almost breaks up Samuel’s (Richard Brooks) marriage and seems to be related to Gideon’s illness. The drama that Harry brings to the family disappears after Suzie grasps the knife that Samuel and his brother Junior (Carl Lumbly) fight with each other. In the end, Harry dies, Gideon recovers and Samuel goes back to the family.

It has adapted several folklore stories into the narrative, not only the traditional folklore roles, but also some modern elements in To Sleep with Anger (1990). This paper will examine the significance of modern folklore in the film.

Take two pieces of traditional folklore in the film as examples: broom and toby. The audience can predict that the film’s protagonist Gideon (Paul Butler) will suffer something bad when the film comes to the scene in which he loses his toby because “toby protects people from illness” (Rucker 15). A similar guess could also be made about Gideon’s old friend from Memphis, Harry (Danny Glover), when his feet were touched by a broom after he just arrives at his friend’s house because “people will have bad luck if he/she is touched by a broom” (Szwed, Abrahams and Robert 21). It turns out that Gideon does become ill and Harry dies in he end. In depicting Babe Brother’s dilemma, To Sleep with Anger calls on its viewers to continue to embrace folklore’s methods and to plumb its rich sources of knowledge.

John Henry

Let’s start the folklore relationship of individual characters from Gideon.

Gideon and his wife Suzie (Mary Alice) reside in a cozy, spacious house in South Central Los Angeles where they still raise chickens and grow vegetables in the backyard in a rural southern way. Suzie works as a midwife; Gideon, whom friends call “John Henry,” has apparently retired with a comfortable pension; they raised their sons, Junior, an industrious family man following his father’s mold, and Samuel — also named Babe Brother — who always wants to get away from his family constraints and his father’s discipline.

Gideon’s nickname is “John Henry,” which can be a signal indicating his authority in his family. John Henry is a legendary as a model of black masculinity. As Alan Dundes has noted, “John Henry is the strong, loyal, gentle Uncle Tom worker, the ideal ‘good nigger,’ whose total strength is devoted to doing the white man’s assigned job. John Henry, strong as he is, constitutes no threat or danger to his white captain.” (562). Dundes emphasizes that John Henry’s vast popularity with Africa Americans is because of his harmlessness. (569)

John Henry dies in a competition with a machine as he tries to prove the superiority of man over technology. Although John Henry proves his point about man’s superiority, in many versions of the tale he primarily “benefits a white employer who has placed a bet on him”. (Odum and Johnson 222)

Like John Henry, Gideon also lives for others, as a father, husband, employee, and church member. As in the Old Testament, Gideon is also referred to as one of the last judges of Israel’s leaders who follow God’s law in serving their subjects.

Samuel sees him as one without personality, whose ego has been displaced or suppressed. Babe Brother comments in a disagreement with Linda: “My daddy never gave me anything without my having to sweat for it. Every summer we had to pimp all of Big Mama’s hundred-odd laying hens and go to church all day on Sunday. For Big Daddy, callouses and sweat were the mark of a man.”

Hairy Man and Trickster

After Harry’s arrival, a lot of weird things happened: eggs and jars suddenly drop and break, a trumpet virtuoso cannot play in tune, an unborn child violently flails in the womb of Junior’s wife Pat (Vonetta McGee), a serious illness attacks Gideon without any clue. These small details suggest that Harry may have some corruptive power and supernatural dark magic to make trouble and mess up other people’s lives.

As Ellen L. O’Brien notes, Charles Burnett based Harry on “Hairy Man,” a Southern folkloric character known for stealing the souls of those who are most vulnerable (114-115). Sojin Kim and R. Mark Livengood stress that Hairy Man’s origins can have additional meaning: the Hairy Man tale most likely emanates from a folklore motif associating with the devil with a hairy man that Stith Thompson has indexed in his well known Motif Index of Folklore (73).

Harry represents a very different version of the past from Gideon: He is a trickster and survives by taking advantage of other people. Like tricksters in many African-American tales, Harry has developed his skill at destroying the established social order.

Among the characters found in African folk tales, the “trickster” is a common one. Though often an animal, it may also be a god, man or woman who is very clever or who creates conflict. The tortoise, snake, hare and spider often display bad human behavior, such as stealing or lying. (Cunningham 127) According to Burnett, Harry is “a character that comes to steal your soul, and you have to out-trick him”(Guerrero 170). As Babe Brother’s wife Linda (Sheryl Lee Ralph) remarks in the film, “you’re not like the rest of Gideon’s friends. Most of them believe if you’re not hard at work, then you’re hard at sin.”

Trickster is more than a cunning character in African-American tales who cheat and use other people. Modern African American literary criticism applies the trickster figure into an example of a possibility to overcome an established system of oppression.

Like African tricksters who “create alliances, which they inevitably break, or who break longstanding ones in pursuit of their own apparent egocentric goals” (Robert 27),

Harry represents the danger, violence, and rebellious masculinity that attract Babe Brother considers these characteristics as symbols of freedom.

Harry has a high ability to intertwine with the past.

There are two alternating and parallel scenes, one when Gideon, Suzie, Junior and his family attend church services and baptisms; another when Harry plays cards with Babe Brother and talks about his violent past in order to seduce Babe Brother, as Linda and Sunny look on.

Harry’s interaction with Hattie (Ethel Ayler) also shows he likes to haunt people with the past:

Gideon: Haven’t the years been good to Hattie?

Harry: It hasn’t been the years; it’s been the men in her life.

Hattie: Harry, that’s not nice. I’m in church now.

Harry: why run out and close the barn door when the horse is gone? I remember when you weren’t saved. That was way back yonder when the Natchez Trace was just a dirt road.

Hattie: some people grow up and change their ways.

Harry: I know your mother ain’t still operating that house of hens.

Hattie: My mother passed one year ago.

He refers to the Natchez Trace, a 400-plus mile route between Natchez, Mississippi, and Nashville, Tennessee, which is a dangerous path. As J. Kingston Pierce notes, the Natchez Trace is also known as “the Devil’s Backbone,” due to the illicit activities-excessive drinking, gambling and prostitution-that took place there (31-32). We can see that connecting Hattie to the Natchez Trace is not accidental, but on purpose: to indict Hattie’s checkered past and show her inglorious roots.

Like Brer Rabbit, Harry breaks the established order, but unlike his animal predecessor, he wants to triumph over it. To do that, Burnett adds to Harry’s character another element of modern Black folklore, the badman. Ultimately, Harry is rejected, but the continued presence of his dead body in the last part of the film testifies to the continued presence of his ideas, a clearly modern folklore approach to a traditional story.

Cain and Abel

The film has ambiguously reshaped the Cain and Abel story by contrasting both with the Biblical model and with Harry’s. When Babe Brother refuses to help other family members repair the roof, a fight breaks out between him and his brother. The fight primarily reveals Babe Brother’s and Junior’s mutually intense hate and their hugely differing values. The fight scene resonates a lot with the Biblical conflict between Cain and Abel. Babe Brother resembles the envious Cain and Junior is Abel.

Babe Brother is self-centered and seduced by Harry’s persuasive arguments for doing the wrong thing. For instance, he doesn’t help to repair the roof when there is a leak; he does not bring Suzie a birthday gift; he slaps Linda over a minor accident. Being a loan officer in a bank presumably shows Babe Brother’s professional competence. He can earn enough money to financially support his desire for fashionable clothes and fancy cars.

Samuel is also bound by rules. Within his own and his parents’ homes, he often questions orders and demands either from his wife or his father. For instance, in a scene in the film, Babe Brother’s wife Linda blames Babe Brother for feeding their son Sunny (DeVaughn Nixon) coffee after Babe Brother has been told the boy cannot have it. Babe Brother boldly ignores Linda’s words and fights with her, indicating his hunger for freedom and his desire to defy the rules of discipline and constraint. Another example is between Babe Brother and his brother Junior. After Linda and Sunny have moved to Junior’s house, Babe brother parks his luxury car in front of Junior’s house and sits locked in it, while his angry brother shouts at him to “grow up!”

Babe Brother’s final return to his family shows his underlying sense of family obligation. In a late scene in the film when Babe Brother walks through the woods with Harry, he seemingly hears his son’s call in the distance. It is also just the time when he sees a dead hawk, a symbol of the failure of the predatory life, and signifying that Harry’s attempt to seduce Babe Brother will also fail.

Unlike Babe Brother, Junior has a high sense of responsibility and family. In contrast to Babe Brother’s materialism, he is so ordinary and plain: Babe Brother wears stylish, elegant fashion clothes whereas Junior dons unremarkable clothes without any brand; Babe Brother drives a luxury cozy expensive sedan while Junior owns an old, large, domestic car.

Junior, like his father, is hotheaded but able to restrain his anger after Suzie’s or Pat’s arguments. Babe Brother, more like Harry, is a catalyst for the other’s self-destruction. Therefore, Junior’s struggle is not only against Babe Brother, but also against Junior. Similarly, Babe Brother is also against his father Gideon.

In using the comparison of Cain and Abel, the film parallels traditional folkloric uses of the Bible to comment on African-American social traditions. The story ends with Junior and Babe Brother’s mutual decision to take responsibility for Suzie and the family as a whole.

The film also applies Biblical references from the beginning, including character names such as Gideon and Samuel, and scenes of apples symbolizing forbidden knowledge eaten by Sunny and Harry. It moves beyond the fraternal division central to the Biblical story; it also denies the spirit of fraternal connection that Harry upholds.

Adam and Eve (Samson and Delilah)

Harry attracts Babe Brother by showing his big knife and implying his willingness to use it. In the process, Harry drives a wedge between Babe Brother and Linda, who quickly senses the “homosocial nature of his experience”(King 478) There is a scene about the images of Harry’s playing cards: Adam and Eve are expelled from paradise while Death stands with a Maiden. This scene is associated with Harry’s dissatisfaction and blame of man’s and woman’s true love as a result of humanity and mortality.

In a late scene of the film during which Babe Brother tells the story of his attraction to Harry, Linda intently plucks hairs from his chest as she listens and repeats Babe Brother’s words. During the initial card game, Babe Brother scolds Linda when she touches one of his cards. In the next card game, after upbraiding Linda for not tying Sunny’s shoes, he slaps her face when she prevents him from cutting the roast before it is ready. Immediately afterwards, he forces Linda, who dislikes joining domestic occasions even for Suzie’s birthday, into a domestic environment and makes her serve dinner to him and Harry and the other guests.

These scenes might “signify her emasculation”(Reynaud 325) and resonates with the Biblical story of Samson and Delilah. Samson and Delilah is a story about love and hate. Samson, a Philistines and the strongest man of the tribe of Dan, successfully enslaves the Israelites. Through by virtue of winning a contest of strength he wins the Philistine Semadar and falls in love with her. But Semadar betrays him, and the betrayal leads Samson in a fight with her real love, Ahtur and his soldiers. Semadar is killed, and her sister Delilah, who had secretly loved Samson without telling him, now wants to get revenge against him for her sister. She seduces Samson into revealing the secret of his strength and then betrays him to the Philistine leader, the Saran. Babe Brother can be viewed as Samson and Linda’s hatred to Babe brother can be regarded as Delilah’s hate to Samson.

Fire

In the opening scene, Gideon is in the middle of a deep sleep and dreams of being consumed by flames as he sits slothfully, in a brilliantly white suit and shoes.

Fire has special origin in the American folklore history. As Chireau mentioned:

In the beginning of the world, it was Bear who owned Fire. It warmed Bear and his people on cold nights and gave them light when it was dark. Bear and his people carried fire with them wherever they went. Man warmed himself by the blazing Fire, enjoying the changed colors and the hissing and snapping sound Fire made as it ate the wood. Man and Fire were very happy together, and Man fed Fire sticks whenever it got hungry. (139)

The flames suggest the possible presence of evil manifested in the form of Harry. When Gideon wakes up, he finds that he is barefoot and has fallen asleep while reading the Bible in the backyard.

The slow dissolve between the dream sequence and real-time hints at the conflict that runs its course throughout To Sleep with Anger: Gideon and his family are embroiled in a struggle between tradition and modernity, between conjure and religion. (Cunningham 123)

Broom

There are several scenes about brooms in the film, which have different meanings.

In the first scene, Gideon’s grandson Sunny sweeps the floor with a broom and then Harry just arrives Gideon’s house. This matches the folklore story in Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s book The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African American Literary Criticism that “When a small child takes a broom and begins to sweep, company is coming”(81). Similarly, Sunny accidentally touches Harry’s feet with a broom, since “Touching anyone with a broom while you are sweeping causes bad luck” and “If you allow children to sweep the floor, they will sweep up unwanted guests” (Gates 82). The audience might later think it somehow takes for granted the at first seemingly surprising consequence that it is Sunny’s marbles that finally bring an end to Harry’s trickster life and death.

Toby

Toby, as one of the traditional amulets, takes the form of an X or cross, congruent to religion and can be wielded for evil purposes.

Gideon and Harry have lost their tobies, which could scare away evil spirits. As Harry says, “You don’t want to be at a crossroads without one… In my travels I misplaced it. I have been looking over my shoulder ever since.”

Without his toby, Gideon and his family have no means with which to maintain the balance between good and evil; thus, they succumb to evil. (Cunningham 119)

After losing his toby, Harry replaces it with a rabbit’s foot. O’Brien indicates the function of the rabbit’s foot in To Sleep with Anger is an object that both protects its holder and probably can be used to “practice evil magic” (120). Chireau writes, “For many blacks, illness was viewed as the work of the devil, and Conjure was associated with the universal contest between the forces of good and evil”(236). Harry has utilized his rabbit’s foot for evil purposes, corrupted his body and corrupted Babe Brother’s soul.

For Harry, life without his toby has been precarious; for Gideon and his family, the loss of the charm brings about misfortune in the form of the wayward Harry, who represents a Southern past that breaks the tenuous hold the family has on peaceful coexistence. (Cunningham 123)

Crossroads

Harry’s recall of the crossroads in the film is regarded as one of the indicators of Harry’s connection to the devil.

As Esu-Elegbara notes:

The crossroads are a standard in blues lore, most notably as the place where legendary bluesmen Robert Johnson and Tommy Johnson sold their souls in blues, the crossroads are therefore the locus of an American. (21)

Another scholar writes:

The interpretational uncertainty represented by the crossroads creates a spatial and temporal realm of ambiguity. This is the realm of the trickster figure. (Jones 19)

Harry mentions the crossroads as a reason for having a toby; he tells Babe Brother, “When we were children, there used to be an old man that came around and would snatch your soul if you didn’t have something on you that didn’t make a X.” It not only indicates the power of the toby, but also the tendency for wrongdoing is in his blood.

Conjure

Gideon’s illness becomes more severe after Harry serves him a bowl of chicken soup. As O’Brien notes, this resonates with traditional African healing practices (120-121). One can deduce that Harry has malicious intent. After Gideon’s doctor cannot alleviate his symptoms, Suzie starts to try home remedies, a form of conjure. When Gideon and Suzie’s preacher (Wonderful Smith) appears with members of the congregation’s to pray for Gideon by his bedside. Suzie displays to them the folk treatments she has given Gideon:

Suzie: I put some Plummer Christian Leaves under his feet to draw the fever out.

Preacher: What else have you been giving him?

Suzie: I crossed his stomach with cold oil and gave him some cow tea.

Preacher: Suzie, I would think you would depend on prayer rather than these old fashioned remedies. Let us read from the Bible.

The preacher and his parishioners disagree with Suzie’s folk prescription and show contempt for she and Gideon continue to use the old traditional ways. Suzie’s attempt to heal Gideon with conjure appears in the form of modern organized religion.

Pigeon

The pigeon usually embodies freedom, when it is in flight. Throughout To Sleep with Anger, many images of homing pigeons are intercut with the family’s domestic drama. That means the pigeon’s freedom is restricted or circumscribed by its home domestication.

The shots of pigeons reinforce a message that the film emphasizes a vision of family that relies on balancing self-restraint and self-fulfillment within the realm of home. It also suggests that Samuel finally learns to embrace a freedom that coincides with home discipline and family responsibility when he leaves Harry and comes back to his family.

Railroad

There is a scene in which Gideon and Harry stroll down the tracks of a railroad on a hot afternoon. As the two men talk about family discipline, they look back on the rails as if to see their past. Suddenly, there are several black laborers who are hammering stakes and working in the railroad. The image recalls a memory of Harry and Gideon working together. As John Henry, Gideon is more closely associated with this work.

Harry is trying to relate the moment to a Southern past. Harry remarks, “I can sit here and look at train tracks all day. We laid enough of them, didn’t we? So many memories are stretched along tracks like these.” As Gideon gazes into the distance, the ghostly scene of men singing a work song while laying tracks appears. However, Harry remains unaffected. The detail that the heat does not weaken him is another suggestion of Harry’s evil nature.

This scene serves as the start of Gideon’s affliction. The next morning, Gideon, a usually strong and healthy person, cannot get out of bed; he has become very ill. On the surface, it seems that Gideon has been weaken by the previous evening’s fish fry and his long walk in the hot afternoon. Indeed he is influenced by Harry’s vicious nature, also as a result of the loss of his toby.

Conclusion

The use of modern folklore provides strong contrasts: Babe Brother’s materialistic values and Gideon’s, Suzie’s and Junior’s very different moral concerns, Traditional and Modernity.

Suzie and Gideon have shaped a way of life based on family, church, and community service, which Junior, his wife Pat, and their daughter Rhonda follow without question. In contrast, Babe Brother and his wife Linda are a mobile, materialistic couple defying Suzie and Gideon’s old-fashioned values.

In To Sleep with Anger, Gideon and Babe Brother both struggle to balance tradition and modernity. The film’s use of the John Henry folktale helps stress this conflict. Gideon is out of modernity as Babe Brother is with tradition. As O’Brien suggests, “In the film, the Baptist church plays a role in symbolizing the difference between traditional ways and modern ways, and specifically, the division among the characters” (118). Of this conflict, O’Brien writes, “Burnett warns us that wherever one’s self definition comes from in terms of cultural values, the individual must learn to live with the new ways as well as cherish the old ways, otherwise that person is vulnerable to evil force” (117). Babe Brother and Gideon lack this balance and are the most fragile figures of the family who are easily affected by Harry’s evil nature. Harry’s dead body remains on his floor for hours in the end of the film. The coroner’s office never arrives to retrieve it. After the neighborhood knows that Harry’s dead body is still in the family’s home, they get everyone out of the house and host an afternoon picnic for Gideon’s family.

By adopting the competing folk legends to describe Harry’s and Gideon’s characters, Burnett continues “a black vernacular tradition of evaluating masculine heroism”. (Rucker 47) As folklorist John Roberts has argued, folk stories and songs have offered functional and dysfunctional models of behavior for African Americans for a long time (37-38).

Neglecting folklore’s contribution to Burnett’s film not only limits our understanding of To Sleep with Anger but also neglects alternatives to Hollywood’s stereotypical ways of discussing black life and identity.

The slow dissolve between the dream sequence and real-time hints at the conflict that runs its course throughout To Sleep with Anger: Gideon and his family are embroiled in a struggle between tradition and modernity, conjure and religion. (Cunningham 123).

Modern folklore in To Sleep with Anger (1990) portrays and tests the feasibility of traditional vernacular African American values in modern society and meanwhile insinuates protagonists’ fate in the film and relevant plots.

References

Gates, Henry Louis Jr.“The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism.” Oxford University Press; 25 ANV edition (July 23, 2014)

Bassil-Morozow, Helena V. “The Trickster in Contemporary Film. ” New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Burnett, Charles. “Inner City Blues.” Pines and Willemen 223-26.

Chandler, Karen. “Folk Culture and Masculine Identity in Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger.” African American Review 33.2 (Summer1999): 299-311. Print.

Chireau, Yvonne. “Conjure and Christianity in the Nineteenth Century: Religious Elements in African American Magic.” Religion and American Culture 7.2 (Summer 1997): 225-246.

Cunningham, Philip Lamarr. “The Haunting of a Black Southern Past: Considering Conjure in To Sleep with Anger.” Southerners of Film. 123-133. Print.

Ellison, Mary. “Echoes of Africa in To Sleep with Anger and Eve’s Bayou.” African American Review 39.1-39.2(Spring-Summer2005): 213-229. Print.

Esu-Elegbara, “The Signifying Monkey and Trickster of West African Mythology.”

Jones, Jacquie. “The Black South in Contemporary Film.” African American Review 27.1 (Spring1993): 19-24. Print.

King, Jeannine. “Memory and the Phantom South in African American Migration Film.” Mississippi Quarterly: The Journal of Southern Cultures 63.3-63.4 (Summer-Fall 2010): 477-491. Print.

Kim, Sojin & Livengood, R Mark. “Film Review Essays: Talking with Charles Burnett.” Journal of American Folklore 111 (Winter 1998): 69-73.Print.

O’Brien, Ellen L. “Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger: An Anthropological Perspective.” Journal of Popular Culture 35.4 (Spring 2002): 113-126. Print.

Reynaud, Bérénice. “An Interview with Charles Burnett.” Black American Literature Forum 25.2 (Summer1991): 323-334.Print.

Rucker, Walter C. “The River Flows on: Black resistance, culture, and identity formation in early America.” LSU Press, 2006. Print.

Szwed, John F., Abrahams, Roger D., Baron Robert. Afro-American folk culture: an annotated bibliography of materials from North, Central, and South America, and the West Indies. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues, 1978. Print.

Ryan, Caroline. “Black History Preserved In African Folk Tales.” February 23, 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.howtolearn.com/2012/02/black-history-preserved-in-african-folk-tales/

[1] Charles Burnett, the director and writer of the film To Sleep with Anger.